Home

Procopio Novera, a "deportado" & the Jai Family

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

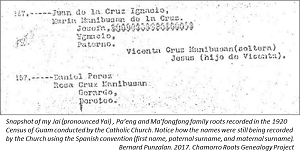

A 1920 church census of Guam snapshot with “deportado” (deportee) information.

During the Spanish occupation of the Mariana Islands and early U.S. occupation of Guam, there were instances of Filipinos being deported to the Mariana Islands for criminal or political reasons.

As with the case of “Procopio N”, a Filipino gentleman, who was a deported to Guam for political reasons (related to the 1896 Philippine Revolution against Spain). It took some additional time and research to discover that his full name was Procopio Peña Novera.

After translating the church census text on Google Translate, it revealed that Procopio and Ana Ignacio Cruz, my maternal Great Grandfather Jai's sister, had one daughter, who they also named Ana (married Juan Pangelinan Santos, manggåfan Bonik).

When all the Filipino political deportees on Guam were allowed to return back to their country Procopio eventually chose repatriation and to reunite back with his wife in the Philippines. However, in De Viana (2004), he indicates that Procopio opted to stay on Guam; but never mentioned that he in fact returned back to the Philippines. Procopio was still on Guam by 1902, based on a land record court case where he made a statement to the court that he purchased a house on Pizarro Street in Hagåtña from Jose Ignacio.

Later after Procopio had left Guam, Tan Anan Jai married Juan “Iko” Pangelinan Guerrero (manggåfan Kotla yan Liberato) as reflected in this church census snapshot.

Bibliography

United States Government. 1902. Civil Case No. 245, Procopio Novera y Peña. Court of First Instance, Guam.

Father Roman Maria de Vera. 1921. Censo Oficial de 1920 (copia). Aragon-Cantabria, Burlada, Spain.

Augusto V. De Viana. 2004. In the Far Islands: the Role of Natives from the Philippines in the Conquest, Colonization and Repopulation of the Mariana Islands. University of Santo Tomas: Manila, Philippines.

Manggåfan Jai: 1920 Church Census of Guam

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

This image is a snapshot of my Jai (pronounced Yai) , Pa’eng and Ma’fongfong family roots recorded in the 1920 Census of Guam conducted by the Catholic Church. Notice how the names were still being recorded by the Church using the Spanish convention (first name, paternal surname, and maternal surname). Also, the Church and Spaniards did not record the married woman's husband's surname; they left the woman's maiden name completely in tact.

This Church census was conducted independently and separately from the 1920 U.S. Federal Census of Guam.

The Guam Genealogist (Publication)

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

The Guam Genealogist published by Jillette Leon-Guerrero, Guamology Inc. is now available. It is a quarterly publication offering insight, tips, tools and resources for those interested in conducing genealogy focusing on families from the Mariana Islands and Guam.

You can subscribe to receive this rare publication at this link:

https://www.guamologyinc.com/store/p71/The_Guam_Genealogist.html

Or...if you are on Guam you can buy a copy at the Faith Bookstore:

https://www.facebook.com/FaithBookstoreGuam/

University of Minnesota Here We Come!

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

Please spread the word to those that might be able to attend. Si Yu'os Ma'åse!

A Call for Biographical Stories of Chamorros Living Abroad

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

Håfa Adei!

Last year I initiated a pilot program to collect, present, and preserve the stories of diasporic Chamorro people and their families residing outside of the Mariana Islands. These stories were presented at the 12th Festival of the Pacific Arts. I am once again excited that this program will continue; therefore, reaching out to invite each and every one who may be interested in submitting biographical summaries of people and families of Chamorro descent.

I have recently been invited to present at an upcoming workshop on Chamorro genealogies, family histories, stories of Chamorro travel and living away from the Marianas, at the University of Minnesota sometime this September 2017 (more information to follow as we narrow down the details).

Some suggestions on the type of information contained within their biographical stories that people have included:

- Person’s name and family name (clan name if known too)

- Village or origin and island the person/family originates

- Accomplishments while at home

- When did the person/family emigrated

- The reason(s) why they left

- Some of the things they accomplishments while away from home

- The number of generations/descendants since the person/family’s arrival

- Name, phone number and email of person submitting the biographical information

- Photos

The list above is not all inclusive of what may be included. Again, part of the intent is to convey and record stories of the Chamorro diaspora for future generations to come and we would like for you to tell the story in your own words. If you need help, we will be more than happy to assist you in writing the story.

Eventually, one of my goals is to publish these stories in a book, so please be aware of this prior to submitting any information. I also envision submitting and filing copies of this presentation with the Micronesian Area Research Center, Guam Department of Chamorro Affairs, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Humanities Council, and the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project.

Please submit all biographical summaries and photos via email to: chamorroroots at gmail.com from now through July 31, 2017.

Page 33 of 84