(The woman is Maxima Dela Cruz Pangelinan)

Background

Since 2003, I have committed myself on this journey to being one of the caretakers of CHamoru genealogy. At first, I was naïve because I did not realize how much I did not know about my peoples’ history. I also did not realize that I had to reconstruct family trees to make sense of our peoples’ stories. Because of this, I came to learn that it also meant that I did not know the definition of genealogy, which is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. It was like a pathetic epiphany. So, here I am continuing to engage in this special awakening and sharing of what I learn as I continue this journey. Generally, I will blog/write brief paragraphs of my preliminary findings. Eventually, I am able to weave them into larger stories. This particular segment covers a few naming practices of the native people of the Mariana Islands.

Historical Recordings

To date, I have been able to find at least three different recordings from contact to early 1800s. The earliest recording I came across was from Fray Juan Pobre. In 1602, Pobre jumped ship and stayed in Luta (Rota) for seven months. During his sojourn he was able to interview Sancho, a Spaniard that was previously marooned in the Mariana Islands and lived among the natives. Sancho conveyed to Pobre what he had observed and learned of the native people and their culture. Pobre (1996) wrote:

“The names which they give themselves from the time they are small are names of fishes or of trees which they use to make their canoes or of other similar things that they value very much.” (p. 182)

June 15, 1668 marks the beginning period of the Spanish colonization. This is precisely when Father Diego San Vitores and other Jesuits backed by a contingent of Spanish Army soldiers planted themselves in the Mariana Islands in the name of Spain. One of the observations of how some of the native males changed their names was recorded by Father Juan Ledesma (1996) in 1672.

“When the latter [brothers and nephews of deceased male] inherit [main house and land], they change their names, adopting that of the founder or elder of their family, respecting the distinctions between the high, low and middle lineages to such an extent that it is amazing to see in people with so little diversity in clothing and housing accommodation.” (p. 480)

However, prior to the arrival of the Jesuits in 1668, the natives only had an indigenous first name. As the Jesuits began recording their experiences some mentioned the Christian names given to the natives (Garcia, 2004). After being baptized, their Christian name became their first name and indigenous name became their surname. Kepuha (Quipuha) became known as Juan Quipuha, Matå’pang’s daughter became known as Maria Assion, So’on became Alsono So’on, Hineti became Ignacio Hineti, so on and so forth.

More than over a century later, it seems that the CHamoru people continued to give their children native first names into the early 1800s. This recording occurred in 1819 during the French Uranie expedition visit to the Mariana Islands from Louis Freycinet (2003). The expedition lasted three months in the Mariana Islands. Freycinet recorded that some of the native children were given names based on the talents or personal qualities of their father, or named after fruit, plants, and other things.

At some point during the 1800s, the practice of giving children native first names, for the most part, discontinued. For the CHamoru people of Guam, Laura Thompson (1947) wrote:

“The godfather and godmother or the parents give the child a name. There is no rule for naming the child, but the first boy is usually christened in honor of a deceased grandfather, a first girl in honor of a deceased grandmother. In fact, children are often named after their grandparents or godparents or patron saint on whose day they were baptized. Frequently, however, a woman in labor prays to a saint for easy delivery. Then she names the child in honor of the saint.” (p. 244)

Thompson also noted that most “Guamanians” are not known by their names but by their nicknames.

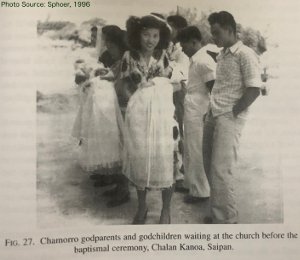

For the CHamoru people of the Northern Mariana Islands, Alexander Spoehr (2000) in 1954 seems to have well captured CHamoru naming traditions of the Spanish colonial period, through and into the initial influence of Americanization.

“Names.—The name given a Chamorro child is selected by the parents. Most given names among the Saipan Chamorros are of Spanish origin, the familiar "Jesus," "Maria," and "Jose" being favorites in the community. The German, Japanese, and now American periods of administration have also left their mark. During German times, "Herman," "Oscar," "Victor," "Wilhelmina," and "Frida" came into favor, though these names no longer are selected with as much frequency. In the Japanese period, the Spanish names continued to provide most of the given names. Japanese names do not fit well into the European name system established among the Chamorros, and I recorded no Japanese names given at baptism. According to informants, in Japanese times when a Chamorro went to a Japanese school he was required to assume a Japanese given name. Students who went on for further training, including those few who went to school in Japan, acquired an entire Japanese name, a process that was looked on with favor by the Japanese authorities as leading to a greater assimilation of Japanese culture. It is doubtful that more than a dozen individuals were affected, however, and they have since resumed their Chamorro names.

Today most Chamorro names are still drawn from the corpus of Spanish-diffused given names. A few names of American origin are making their appearance and others are being Anglicized, for example, "Guillermo" to "William." In most cases single names are given, but a few double combinations have appeared in the last few years, two examples being "Victor Segundo" and "Evelyn Ruth." On the whole, however, the Spanish tradition survives as the main source for given names.” (p. 239-240)

The impact of colonization and assimilation on CHamoru naming traditions is quite apparent. It demonstrates the decline of ancient CHamoru naming practices and the shift towards the influences of the colonizer’s practices.

References:

Freycinet, L.C. (2003). An Account of the Corvette L’Urainie’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands (translated by G. Barrett, trans.). Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI): CNMI Division of Historic Preservation: CNMI

Garcia, F. (2004). The Life and Martyrdom of the Venerable Father Diego Luis de San Vitores, S.J. (M.M. Higgins, F. Plaza and J.M.H. Ledesma, trans). Mangilao, Guam: University of Guam

Ledsma, J.M.H. (1996). The Native Customs of the Chamorros. (R. Levesque trans), History of Micronesia: Focus on the Mariana Mission, 1670-1673, 5. Quebec, Canada: Levesque Publications

Pobre, J. (1996). The Story of Fray Juan Pobre’s Stay at Rota in the Ladrone Islands in 1602. (R. Levesque trans.), History of Micronesia: First Real Contact, 1596-1637, 3. Quebec, Canada: Levesque Publications

Sphoer, A. 2000. Saipan: The Ethnology of a War-Devastated Island (2nd ed.). Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Division of Historic Preservation

Thompson, L. 1947. Guam and Its People (3rd ed). Binghamton, NY: Vail-Ballou