Home

#Weavers as an Occupation

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

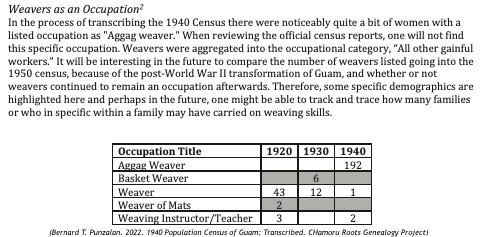

In my 1940 census transcription book, someone noticed that I had place a “#” (hashtag) next to certain people’s names and inquired about it. Because I opted to only publish limited data from the enumerated sheets, I did not publish people’s occupations. Those people with a hashtag mark were weavers.

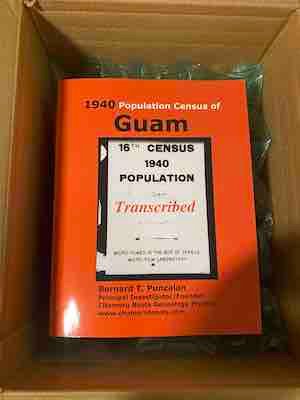

Below is an extracted image from my book recently published.

About the 1950 Population Census of Guam Transcription Project…

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

Yesterday I put out a call for transcription volunteers on FaceBook. I acquired 9GBs of images of the 1950 population census of Guam from the National Archives and Records Administration after its release on April 1, 2022.

I am elated by the number of people who have sent me their interest to volunteer and help transcribe the 1950 population census of Guam for the CHamoru Roots Genealogy Project. I am also floored by one particular notice of interest, which includes an on-going discussion of possibly some students becoming a part of this transcription project and credited as part of their curriculum. This was one of my visions with the CHamoru Roots Genealogy Project to make all this data available to young academic scholars so that they can write and publish our stories. I really hope this pans out for the students. The ultimate beneficiaries of the CHamoru Roots Genealogy Project are always our children’s children.

I am, however, still organizing the details for this particular transcription project, but hope to have it finalized within a week and then schedule Zoom sessions to orient all volunteer transcribers.

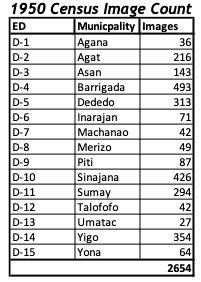

As you can see in the photo, there are 2,654 images. Generally, each enumerated district (ED) population sheet contains up to 25 lines of names and information. While some sheets are not all complete and some may even be blank, we still have a lot of transcription work to do. In fact, there are about 59,498 names that need to be transcribed. For now, I can say that the transcription work will consist of viewing each image and transcribing the data onto an Excel spreadsheet.

There are many other opportunities in this project. Although this project is driven primarily on love time, it remains alive as a result of donations, website subscribers and collaborations. I appreciate all of you who have helped in one way, shape or form to get this project where it is today.

1950 Census is Online!

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

The moment we have been waiting for...https://1950census.archives.gov/search/?page=1&state=GU

Will begin the transcription process in the next few months...

1940 Census Transcription and Index Books Available

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

The 1940 Census Population of Guam: Transcribed and Index books are now available for sale on Amazon. Just search on my name "Bernard Punzalan," and all the books will appear. All proceeds go to the maintenance of this website and project costs. Thank you for your continued support! Si Yu'os ma'åse!

Some Notes About the 1950 Census of Guam

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

The release of the 1950 Census images to the public remains scheduled for April 1, 2022. Once again, I do have plans to put a team together to transcribe the census for the CHamoru Roots Genealogy Project. If all goes well, I hope to have the transcription book published sometime next year.

A few notes/observations about the population of Guam in 1950…

- See my previous article, "Expected Release of the 1950 Census."

- Total population = 59,498. More than doubled from 1940, which was 22,290. The shock growth is attributed to the militarization and refortification of Guam because of World War II. Thousands of military and contractors were brought into Guam immediately after WWII. Note the influx of Filipinos. Many were skilled contract workers, mostly recruited from the Philippine province, Iloilo.

- There were 15 Municipalities. The Municipality of Barrigada had the largest population, surpassing the Municipality of Agana, which was the largest in 1940.This will be interesting to compare with the 1940 census pre- and post-WWII. The transformation of Guam involuntarily displaced many native people from their original homes.

- Although Guam was a U.S. Territory, natives, classified as those born on Guam at the time of the census, were only U.S. nationals and not U.S. citizens until naturalized. It would be later that year, in 1950, were federal law would finally naturalize all natives born on Guam. However, the census Form P85 does include a question if the person was already a U.S. citizen.

- On June 30, 1950, The U.S. Department of Commerce released a preliminary population count of 58,754. The final official population count of 59,498. The difference is not surprising but something researchers should be aware of. My transcription numbers from previous census periods do not match with the official count. Primarily, because I transcribe every name, which includes those that were crossed out on the sheet.

- The census Form P85 contains questions about serving in the U.S. Armed Forces, during World War I, World War II or any other time. I suspect that there will be some level of correlation between those who were veterans and became naturalized during their term of service.

Stay tuned…Will put out a call for volunteers to transcribe and index the 1950 Population Census of Guam sometime later this year.

Page 15 of 81