Home

United States Naval Career of Jesus Arriola Leon Guerrero: 1 December 1937 - 2 December 1957

- Details

- Written by: Arthur W. Meilicke

I have chosen to write about this period of my father’s-in-law life in a more formal manner, using his given name rather than, “Pop,” as the family referred to him, or “Chu.” In the event that other than family members or younger descendants read this document, it is important that they know the name of the man who lived these events and, as best as we can, how he lived them. “Your life is a work of art, and in the end, the underlying theme of great art is bravery and hope and love.” -- Garrison Keillor Jesus Arriola Leon Guerrero created his work of art.

I knew that Jesus served in the U.S. Navy during World War II and Korea, but I knew very little about the details of his experiences or service. His children didn’t know much about this period either. Navy Muster Rolls from 1939 -1949 found on Ancestry.com documented the ships upon which Jesus served during World War II. Researching the history of these ships provided some insight into what he may have experienced, but what one might imagine would be entirely speculative. There was no information about his service beyond 1945. As my curiosity peaked, I wanted to find out more about Jesus’ service, so I recommended Elizabeth (for younger generations reading this, his daughter) request a copy of his Official Military Personnel File (OPMF.) When the record came, examination of the documents provided specific details about his service, to include battles and campaigns in which Jesus participated, commendations, and medals awarded. I soon discovered, however, that there were a number of omissions and errors in his OMPF as service/battle stars earned were not accurately noted or documented, that other awards for which he was eligible were not awarded, and in some cases not recommended. His extensive amount of sea duty was not noted either. (~Art Meilicke)

*Reproduced by permission of the author.

Leveraging Zoom: Database Demonstration

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

Håfa Adei!

In the past I launched a few FB Live pilot demonstrations of the CHamoru Roots Genealogy Project, but I wasn't convinced that it was effective enough for an interactive engagement with attendees. As a result of our recent situation in dealing with COVID-19, I started to revisit the potential of demonstrating the features of the Project’s database and collaborative opportunities via web conferencing.

I am going to give Zoom a try and will be sending out additional information soon on how to sign-up and attend a one-hour Webinar. If you have never used Zoom, now is a good time to check out their website (https://www.zoom.us) to become familiar with it and also determine if your device may need to install their Zoom App.

My current plans to conduct the Webinars will be based on demand and cycled on Sundays and Thursdays: 12:00noon (CHamoru Standard Time for Guam & CNMI), which is also on Saturdays: 7:00pm (Pacific Time). I am still learning to navigate and administer Zoom so the pilot dates for this event are pending.

Stay tuned, more to come.

POSTPONED TBD: Håle’ CHamoru ~ CHamoru Roots Genealogy Workshop

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

Håfa Adei Everyone,

I suppose there should be very little surprise that I must postpone the Håle’ CHamoru ~ CHamoru Roots Genealogy Workshop. I will be issuing refunds to everyone who pre-registered.

I will also reschedule and announce a new date for the workshop once these challenging times have passed through.

Please remember that we are always in God’s hands, continue with your prayers, and sustain all faith that these challenging times, like all others, will pass through. God bless you all and as always thank you Saina for another day!

Bernard Punzalan

Founder/Principal Investigator

CHamoru Roots Genealogy Project

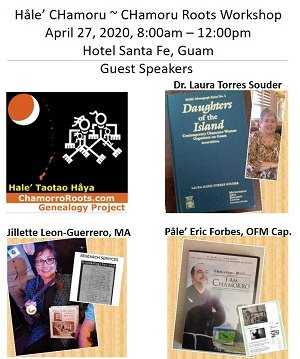

Workshop Guest Speakers

- Details

- Written by: Bernard Punzalan

|

Yes, I would like to attend the workshop. Light lunch included. Reserve my seat. |

No, I will not be able to attend but would like to take advantage of the promotion special for a one-year access to the database and four (4) census eBooks. |

Ok folks, right now I have blessed to secure an awesome trifecta of guest speakers for the Håle' CHamoru - CHamoru Roots Workshop, April 27, 2020, 8:00am-12pm, Hotel Santa Fe, Guam.

Dr. Laura Torres Souder, CHamoru historian, former museum curator, and author of “Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Chamorro Women Organizers on Guam," 1987.

Jillette Torre Leon-Guerrero, MA, CHamoru historian and genealogist, owner of Guamology Inc., gold medalist winner for publishing “A Year on the Island of Guam,” 2019.

Påle’ Eric Forbes, OPM Cap., CHamoru historian and genealogist, who was featured and narrated the documentary video, “I Am Chamorro,” 2015.

Seating is very limited. I encourage you to reserve your seat in advance by clicking on the following link: https://www.chamorroroots.com/v7/index.php/75-workshop/645-chamorro-roots-genealogy-project-workshop-announcement-2

More about Dr. Laura Torres Souder:

https://www.guampedia.com/laura-t-souder/

More about Jillette Leon-Guerrero:

https://www.guampedia.com/jillette-leon-guererro/

More about Påle’ Eric:

https://www.guampedia.com/eric-forbes/

Finding Apolonia

- Details

- Written by: Jillette Leon-Guerrero, MA

Introduction

Proving the parentage of individuals born in Guam during the 1800s is difficult, and in some cases, appears impossible. Finding any written documentation for those born during this period is a challenging endeavor. This is because much of the written documentation for this period did not survive. Guam’s turbulent history, the tropical climate and the devastation of World War II are responsible for the dearth of information.[1],[2] This presents a challenge to genealogists and requires them to use creative strategies to assemble evidence in support of their research. Unless a hidden cache of historical documents is found to bridge this gap, this will continue to confound genealogists and historians for years to come.

In Guam, many families do not know much about their ancestors that lived in the early 1800s. One significant event that may have contributed to this situation was the worldwide influenza pandemic in 1918-19. Brought to Guam onboard the military transport ship the USS Logan, the “Spanish Flu” killed over 6% of the island population.[3] The very young and the elderly were especially vulnerable. Because of the high rate of mortality in the elderly, it has been said that over 80% of those who spoke Spanish perished because of the epidemic.[4] While this event brought an abrupt halt to the use of the Spanish language on Guam, it is also believed to have hindered the transmission of family histories from one generation to the next. For today’s elderly, it is not uncommon for Guam residents to not know who their great grandparents were. For those that do, they know very little about their lives. This was the case with Apolonia Ada.

Reproduced by permission of the Author for research and educational purposes.

[1] Safford, W.E., “The Mariana Islands Notes compiled by W. E. Safford: From Documents in the Archives at Agaña, the Capital of Guam, from early Voyages found in the Libraries of San Francisco, California,” (bound transcript 1901, Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam) p. IV-V.

[2] O.R. Lodge, “Attach Preparations,” The Recapture of Guam, (Fredericksburg: Awani Press Inc., 1988), 33.

[3] Shanks, G.D., Hussell, T. and Brundage, “Epidemiological isolation causing variable mortality in island populations during the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic”, Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 6 (January 2012) 417-423.

[4] Julius Sullivan, “Men of Navarre,” The Phoenix Rises (New York: Seraphic Mass Association, 1957), 118-119.

Page 22 of 81